Following the Money: Researcher Tracks Bitcoin Movements and Anonymity

This article is the first of a two-part interview with University of California-San Diego researcher Sarah Meiklejohn on her new research paper, "A Fistful of Bitcoins: Characterizing Payments Among Men With No Names."

Due to murky regulations and a lack of awareness among major law enforcement entities, for victims of bitcoin theft, there aren't many places to turn to seek justice. One of those places, however, is University of California-San Diego (UC-SD), which is home to researcher Sarah Meiklejohn.

Law enforcement agencies and media outlets turn to the PhD candidate to trace bitcoin movements, because Meiklejohn – along with a team including other UC-SD researchers and those from George Mason University – has dug deep into the block chain, following the money and challenging the notion that bitcoin transactions are anonymous.

Meiklejohn's paper, “A Fistful of Bitcoins: Characterizing Payments Among Men With No Names,” provides a snapshot of the bitcoin economy as of April 2013.

The paper also describes how Meiklejohn's team sleuthed out bitcoin addresses by making transactions and deposits, then used heuristics to link clusters of addresses, following money from a supposedly anonymous marketplace such as Silk Road all the way to an exchange such as Mt. Gox, which if subpoenaed would have to turn over users' real names to authorities.

In light of these findings, we sat down with Meiklejohn in an antique shop/cafe in San Diego to talk about her dealings with bitcoin and whether the currency can truly be used anonymously.

CoinDesk: Do you own any bitcoins yourself?

Sarah Meiklejohn (SM): We bought a bunch of bitcoins with the grant money... one of the things I bought was 10 of the physical bitcoins, Casascius Bitcoins. We have these weekly reviews so we decided to give out a bitcoin to whoever gave the best presentation.

But if you gave any presentation, that was the best one by default. So we had to stop giving out the bitcoins, because we were giving people like $80 [the exchange rate at the time] to show a graph.

I earned one of those bitcoins for my presentation. I cashed out right away... and got 80 bucks. [laughs] I guess I could have waited and done better.

When we first bought bitcoins, [the exchange rate] was like $5 a bitcoin, so we've done well for ourselves there. [On Nov. 8, when this conversation took place, one bitcoin was worth $288.71.]

We bought a bunch more later, probably at more like $15. The rise in the price has been pretty outrageous. We bought about 25 bitcoin [and still have many of them].

CoinDesk: What will your research group do with them?

SM: That's a good question. I've been talking to people about different follow-up projects. But it's not clear that any of it will involve actually spending bitcoins.

For this project, we didn't really have to spend much. Our biggest hit was Bitmix, one of these mixing services, which just stole 10 bitcoin from us. [CoinDesk attempted to contact Bitmix but so far has not received a response.]

But all the stuff we bought was kind of junky, it didn't cost all that much. For the exchanges, we didn't even need to spend anything, it was just deposit/withdrawal.

CoinDesk: Can you sum up your bitcoin research for us?

Sarah Meiklejohn (SM): The two broadest questions we were trying to answer were, one, what are people using bitcoins for? There are all these legitimate vendors - BitPay signing up companies like WordPress - and we wanted to see how prevalent that was relative to anything else.

The second question, which was more security focused, surrounded bitcoin's potential for anonymity. Bitcoin uses these pseudonyms, and in theory the behavior of your pseudonyms doesn't have to be linked – if you're careful. But the question was, how much is this potential for anonymity actually achieved?

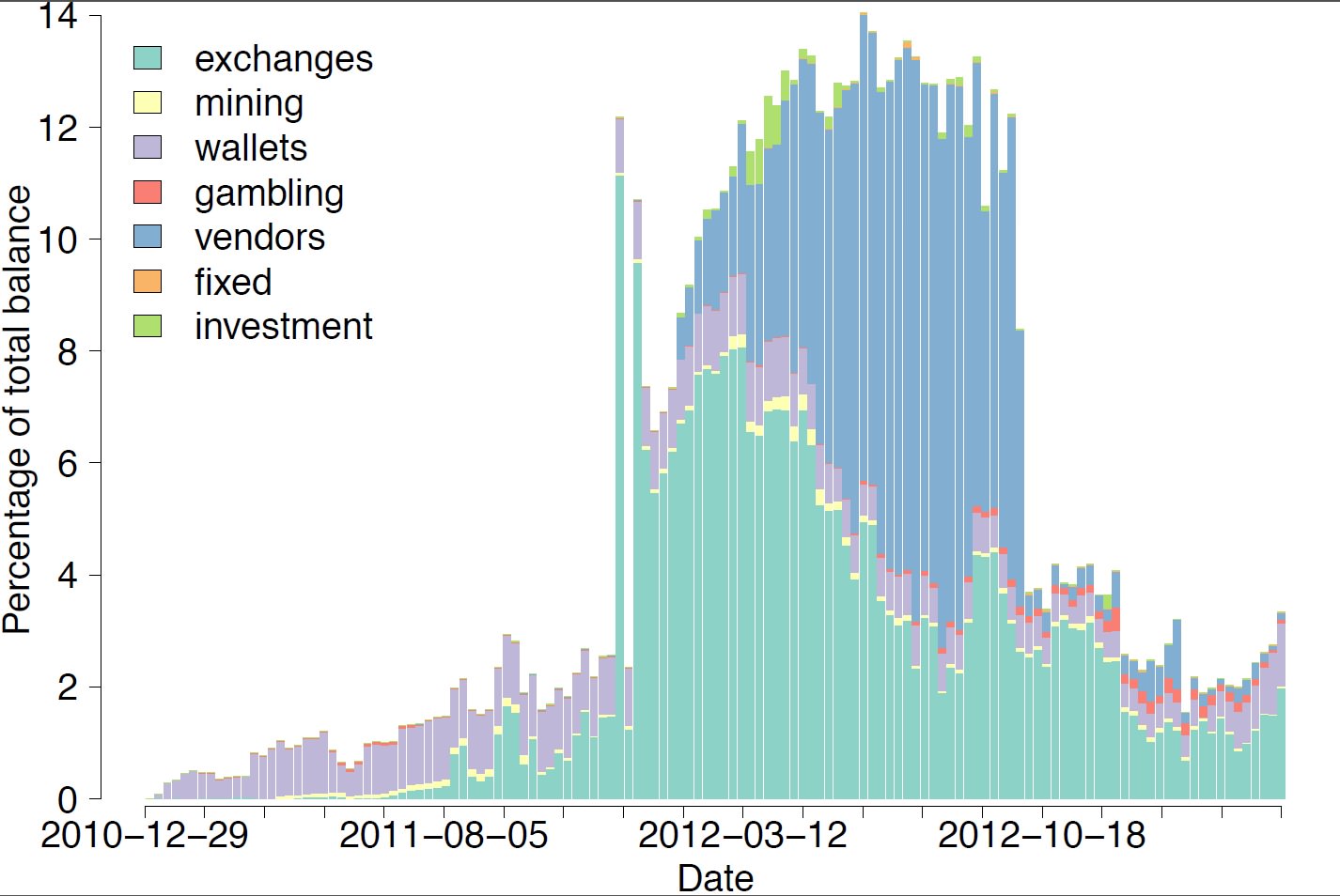

Most active bitcoins are found in these locations.

CoinDesk: What did you learn about the whole bitcoin economy landscape that surprised you?

SM: It's really concentrated in a small number of places. Our numbers are from back in April - I would expect that things have shifted at least a bit, just because of changes that have happened in bitcoin over the summer.

As was pointed out by an older paper by [Dorit] Ron and [Adi] Shamir, the majority of bitcoins are not moving; they're sitting in these addresses. You can speculate however you want about what that means – either they're hoarded, they're lost, they're the cold storage for different exchanges, we don't know.

There's no way of knowing. We did see some movement in these, I call them “dinosaurs.” When they did their research, in May 2012, Ron and Shamir said about 76% of bitcoins were being hoarded, and even when we re-did their analysis this year, it was already down to 64%. I expect that number to keep changing, especially given what's happening with the exchange rate.

So first of all, the majority of bitcoins aren't even circulating. The other thing was how quickly the remaining bitcoins were circulating.

If there are only 4 million BTC in circulation, we saw - again this is all back in April - that a total of 1.2 trillion BTC had been transacted. So that means that all these circulating bitcoins have been spent many, many times over.

The other phenomenon that we had to include in the paper, just because it was so outrageous, was SatoshiDICE and dice games in general. The transaction volume completely dwarfs everything else, but then at the same time, the amounts that are being spent are tiny - it's fractions of bitcoins. That was fascinating.

The other thing that I thought was interesting - and again I'd expect to have changed even since April - is this rise in instantaneous transfers.

With SatoshiDICE, the second you click send, you get your (winnings) back. They're taking this double-spending risk here... as a result there has been some double spending on SatoshiDICE - a small amount.

It's the same with BitPay - the second you click send, they say, “We got your bitcoins.” That's actually a nice trend - as long as you're a big company and you can build this into your cost of doing business, it really provides a big service to your users.

Because when we were doing our transactions, depositing into an exchange, withdrawing them, sitting there and waiting an hour before we could move them again was a real pain.

CoinDesk: As far as anonymity, you came to the conclusion that it's not that easy to stay anonymous with bitcoin?

SM: Actually, I'm not sure that that's the right conclusion. I think that if you are motivated and if you understand how the Bitcoin protocol works, you can stay anonymous.

The caveat there is that you have to try to stay anonymous at scale. If you have a bitcoin, then sure, you can stay anonymous. If you understand the protocol, if you use mix services or other crazy stuff, you're going to do fine.

The problem is when you try to scale this up, if you have millions of dollars worth of bitcoins, then it's going to become a lot harder to hide that number of bitcoins in the network.

When we ultimately went to track some of these big thefts, we saw these attempts to do crazy things like splitting the bitcoins, then peeling them, then aggregating the bitcoins back together - but ultimately the fact that every transaction was publicly available was going to shoot you in the foot when you try to obscure the flow of large amounts of bitcoins.

CoinDesk: Getting back to your “Fistful of Bitcoins” paper, can you sum up, in layman's terms, how your research followed bitcoins from one transaction to another and partially broke through the anonymity of bitcoin?

The idea was that if I'm depositing, then Mt. Gox will give me a deposit address and I'll say “Oh, that's Mt. Gox's address”. I can then label that as definitively belonging to Mt. Gox.

Similarly, when I withdraw the bitcoins, I can go look at the transaction and see the sender and say, “That's Mt. Gox too”. This basically allows us to identify a very minimal amount of ground data.

We next tried to cluster different addresses together, using two clustering heuristics that we described in the paper.

The first one was really standard, a lot of people have used it, and the idea was that if any addresses have been used as inputs to the same transaction, then they have to be controlled by the same user.

[For example,] someone needs to send someone 5 BTC and they have 1 BTC in each of five addresses, and they pool those addresses together to pay it. This is kind of a standard thing in the protocol... this is a very safe heuristic, there are very limited cases in which this heuristic would be violated. It's acknowledged in the protocol by Satoshi.

The second one is based on the idea of making change. Let's consider, I still need to send someone 5 BTC, but instead of having 1 BTC in each of five addresses, I have 6 BTC in one address.

By the properties of the Bitcoin protocol, I need to send those 6 BTC all at once. I can't just spend 5 of them. What I can do, functionally, since obviously I don't want to overspend, is create a transaction with two outputs.

One of the outputs is the legitimate recipient, for 5 BTC, and the other output is an address I own, to which I send the excess 1 BTC. That's the change address.

Again, this is a well-established property of bitcoin that these change addresses are going to be prevalent. The heuristic is: The change address in the transaction belongs to the same person as the sender. That's great - if you can identify change addresses. That is the really tricky part, and probably the bulk of the work of the project went into making this heuristic conservative.

This heuristic was really helpful in identifying certain patterns in the network.

For example, what we call in the paper, peeling chains. The idea is, I take a big amount of bitcoins in one address, I spend a tiny amount and I peel the bulk of the coins off to a change address and that continues.

For example, think about a mining pool getting the 25 BTC reward and then paying its miners. This pattern is really common in the bitcoin network, and the idea is that without identifying these change addresses you can't follow the money at all.

CoinDesk: Are there cryptographic technologies that people could be using to make bitcoin more anonymous?

SM: There was this paper published this year, “Zerocoin: Anonymous Distributed E-Cash From Bitcoin,” out of Johns Hopkins University that layered certain cryptography technologies on top of bitcoin to give provably secure anonymity guarantees. Unfortunately, the big caveat with their work is that it's a lot less efficient.

image via Shutterstock

In some sense, bitcoin was this big slap in the face to traditional cryptography. On its face, bitcoin shouldn't work. It's just signatures and hashes, and it's really amazing that it works, and I think the design of it is incredible.

It's kind of dead simple. I also think that that's part of the reason that it actually got widely adopted -- anyone can understand it, if you take 10 minutes and explain how it works.

It's intuitive, and it makes a lot of sense. Whereas, traditional cryptographic e-cash doesn't make as much sense. Bitcoin is an interesting wake-up call as a cryptographer.

Another project I'm interested in is exploring the provably secure aspects of bitcoin, and the relation between bitcoin and existing cryptographic e-cash schemes that use a lot more heavy machinery.

CoinDesk: In light of your research, how do you feel about the future of bitcoin? Do you feel more confident about this system, or less, after examining it?

SM: The thing that makes me the most nervous right now is this volatility and this low trading volume, and the fact that these big whales with thousands of bitcoins can really affect the price single handedly.

That kind of stuff makes me a little nervous. It's a chicken-or-egg problem. You need more people to adopt bitcoin in order to stabilize this, but people are shying away from bitcoin because they perceive it as volatile and as a risky investment.

The other thing is, it would be important to see more legitimate uses of bitcoin. Its biggest problem right now is there's no clear reason why I should start using bitcoin. I'm happy enough with my credit card.

Unless you really, really care about privacy, the barrier to entry for bitcoin is pretty high. It's not that usable, you can't walk into a coffee shop - at least outside the Bay Area - and buy stuff with bitcoins. I know there have been startups geared to this, but right now it's a little clunky.

Even if I can walk into a coffee shop and buy something with bitcoins, there's not a great mechanism for doing that. Unless you're both using the same wallet service and they have great Wi-Fi, it's a little tricky right now.

I think the usability will have to be higher, I think there will have to be more legitimate services that accept bitcoins, and I think the volatility will have to be lower.

I think that people aren't adopting bitcoin because these things aren't happening, and these things aren't happening because there are not enough people using bitcoin.

It's tricky. I don't know what will happen to bitcoin. I think it's a nice first step in a certain direction – and maybe it'll be more than that.

You can now read the second part of the interview, where Meiklejohn discusses her findings related to Silk Road and online black markets.

DISCLOSURE

The leader in news and information on cryptocurrency, digital assets and the future of money, CoinDesk is a media outlet that strives for the highest journalistic standards and abides by a strict set of editorial policies. CoinDesk is an independent operating subsidiary of Digital Currency Group, which invests in cryptocurrencies and blockchain startups. As part of their compensation, certain CoinDesk employees, including editorial employees, may receive exposure to DCG equity in the form of stock appreciation rights, which vest over a multi-year period. CoinDesk journalists are not allowed to purchase stock outright in DCG.