Money Reimagined: Inflation Is Here? Always Has Been

A quick programming note…

Michael Casey is away. Writing the main essay this week is Adam B. Levine, CoinDesk’s managing editor of Podcasts. He discusses the reappearance of inflation in the U.S. economy and the long-running ways in which elites in Washington, D.C., and Wall Street tend to downplay the threat. The debate, of course, is important for how people think about bitcoin: if prices are rising faster than official statistics suggest, a fixed-supply cryptocurrency is likely to become more attractive to investors and users.

This week’s “Money Reimagined” podcast is taken from a recording that Michael and co-host Sheila Warren made during CoinDesk’s Consensus conference in May. It looks at the growing demands for companies to comply with environmental, sustainability and governance (ESG) standards and how blockchain technology could help them do that. The episode, which is divided into digestible segments, features appearances from Meltem Demirors, chief strategy officer of CoinShares, Mike Colyer, CEO of Foundry (a miner and sister company to CoinDesk) and Julius Akinyemi, founder and CEO of UWINCorp, among other guests. Have a listen after reading today’s newsletter.

The CPI's False Comforts

After a long period of complacency in the U.S. about inflation, the threat has suddenly reared its head. But look closely and you’ll see it's been there all along.

It’s an article of faith among mainstream economic observers that we live in an era of low inflation – in other words, that the purchasing power of the dollars in your bank account have held fairly steady, especially compared to the period of historically high inflation in the 1970s and early 1980s.

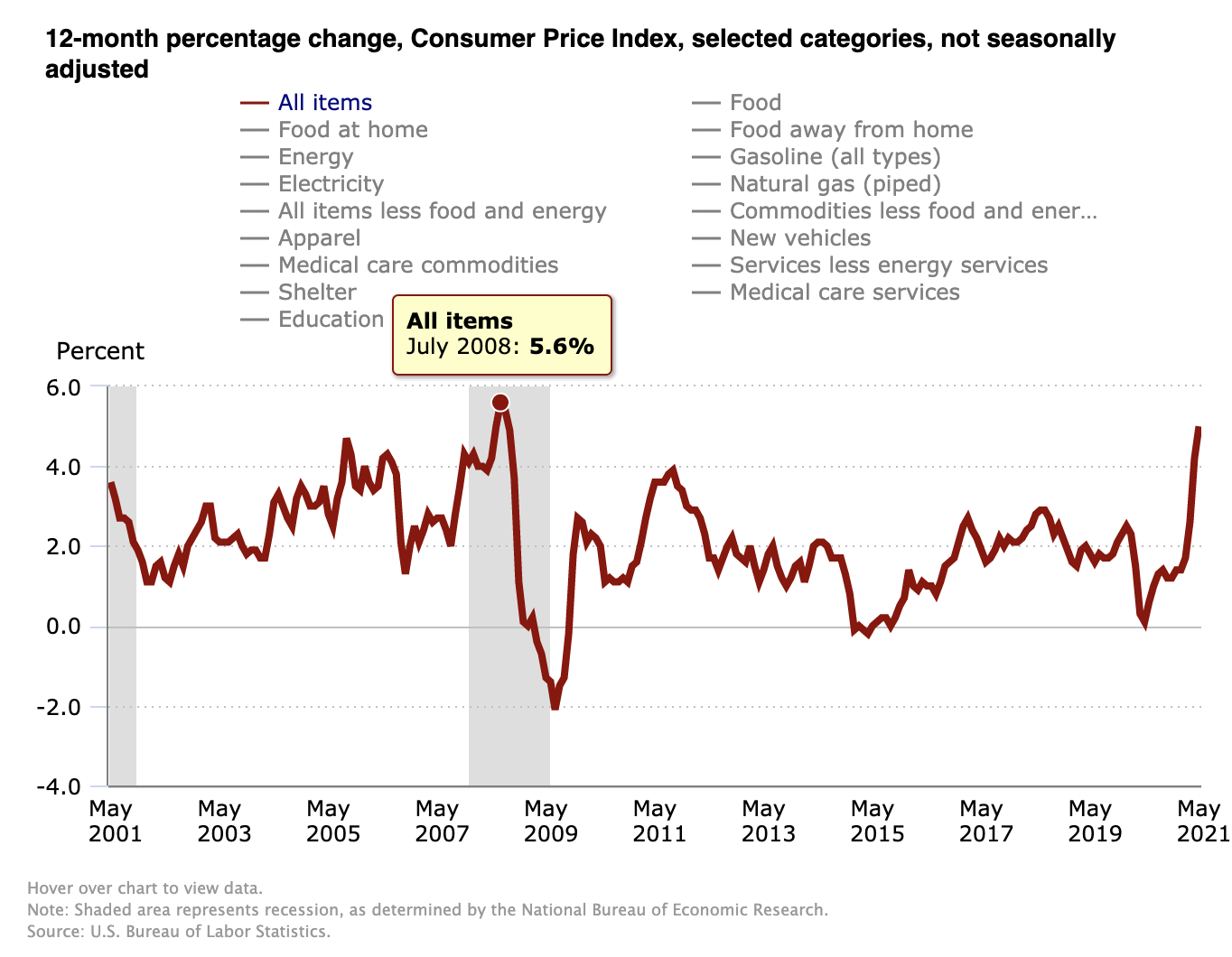

Just look at the consumer price index (CPI), the pundits will say. By that measure, they’re not wrong. Since 2001 official inflation, as measured in 12-month changes in the CPI, peaked at 5.6% in July 2008, and only briefly, before plunging to negative levels in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

This goes a long way toward explaining why goldbugs and their intellectual heirs in the Bitcoin community are mocked as cranks by the “blue check” class. Inflation? What inflation? From this perspective one of the vaunted use cases for the original cryptocurrency – a store of value that can’t be debased by central bankers’ printing presses – may be relevant in Venezuela but surely not in Virginia or Vermont.

Lately, inflation concerns don't seem quite so risible, even by the accepted measurements of the Washington and Wall Street intelligentsia. As the economy recovers from coronavirus-related lockdowns, we’re closer to that peak post-2000 rate than at any time since, with May 2021 CPI clocking in at a toasty 5%.

This inflation, which the U.S. Federal Reserve calls “transitory” (Beltway-speak for “temporary”), comes at a time when the traditionally obvious activity of collecting interest on your savings from your bank yields effectively nothing. The extremely low cost of money comes courtesy of the continued extraordinary monetary policy experiment underway at the U.S. central bank, whose congressional mandate is to maintain “full economic employment and stable pricing,” which the Fed says means keeping inflation at around 2% per year.

To be clear, 5% inflation means that, in broad terms, what cost a dollar in May of last year costs a dollar and five cents this year. In practice inflation is lumpy; some areas like energy and airline fares have seen massive increases of 30% and 24% year over year while a pair of items (medical care commodities and alcoholic beverage components) saw small drops (-1.9% and -0.2%, respectively). These changes in price are then weighted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (the BLS) to create the modern CPI.

The CPI is one of the most important ways that we measure how our world is doing and is vital when planning for the future. In fact, CPI is so important that in 1972 Congress tied it to cost of living adjustments (COLAs) for government support programs like Social Security.

When inflation eats away at purchasing power, COLAs adjust the amounts beneficiaries receive, providing more money to keep things fair and purchasing power predictable. The goal is to ensure that someone who receives Social Security today will be able to afford the same standard of living, taking inflation into account, for as long as the person receives the entitlement.

Which makes sense – if you’re giving people $1,000 per month because that’s how much additional support they need to live, the value of that money dropping each year puts the goal at risk.

And so, perhaps naively, I was floored recently when I set out to understand the history of how we calculate this all-important metric and how those calculations have changed over time. What I found can plausibly be described as political calculus run amok and the most serious case of missing the forest for the trees to beset the American people in my lifetime.

Flashback

By all accounts, the 1970s were a rough time for purchasing power. I wouldn’t know – I was born in 1984 – but history tells us it was an era of escalating prices and myriad government attempts to ease that pain.

Prior to 1975, COLA adjustments for programs like Social Security were set by Congress, which made it a bit of a Sophie’s Choice situation. Congress could vote to increase amounts paid to recipients that would keep purchasing power stable, at the cost of an ever-growing portion of taxes being used for that purpose. Politically there was no winning choice, just a question of who you most wanted to avoid angering.

In 1972, Congress hatched a plan to automate the process and offload the decision to the BLS, which maintains CPI, the official measure of inflation. Starting in 1975, we’d put our best data to work, scientifically determining whether and how much Social Security benefits should be increased or, at least in theory, decreased to provide that consistent, stable standard of living.

In practice, this only made things worse. Between 1975 and 1982, annual cost-of-living adjustments were between 5.9% and 14.3%. Over just seven years, government spending for social security alone increased by a total of 94.43%.

This was, as you might imagine, a huge problem that quickly turned political. It was also a problem that had no good solutions, really just two bad ones. Congress could unhitch COLAs from CPI, at which point politicians would reclaim control over the decision and bear responsibility for whether and how much to change payments. Alternatively, it could leave the automated adjustments in place. Given how long inflation had run and the repeated failed attempts to control it in the 1970s, it was more than feasible that all the money collected in taxes could eventually, and not too distantly, go toward paying for programs like Social Security.

The story goes that in the early 1980s “inflation was tamed” by the legendary Fed Chairman Paul Volcker. But concurrent with Volcker’s actions, the BLS embarked on the first of a series of changes in how inflation was measured.

These changes to the math and methodology used to calculate official inflation, without exception, decreased the readings.

Even if we assume these changes were necessary refinements to bring the CPI measurement closer to reality, they made it impossible for mainstream economics to compare our present with our past. Very few even independent economists still calculate the CPI using original BLS methodologies but everybody still calls our official measure of inflation the “Consumer Price Index.” This means that when you ask a mainstream economist if inflation today is as high as it was in the 1970s, that person will tell you it’s not, referring you to the modern CPI as if comparing a reading from today’s modified inflation measurement to the original are equivalent.

The BLS is a fact-finding agency, and the principle of charity (or at least Hanlon’s razor) requires us to assume until proven otherwise it made these changes in good faith. But looking at the effect of its decisions, one could be forgiven for drawing this conclusion: Because the government couldn’t change actual inflation, it changed the way it was measured and talked about it to make it seem like there was less of it.

If so, politically speaking, this was brilliant. The government slowed the rate at which spending for our most needy grew without the backlash that would rightly come from abandoning them to an ever-declining standard of living.

By any non-political standard, this would be, in my book, one of the biggest, most regressive scandals you’ve never heard of.

In the nearly 40 years that have followed, the difference between actual inflation as the BLS measured it before 1983 and inflation as officially measured for COLA purposes has exploded. It’s exactly the outcome the 1975 CPI-COLA tie was designed to avoid: a declining standard of living for society’s neediest, because the money they are paid is worth less. Its impact goes far beyond government programs, with CPI-driven cost of living adjustments finding their way into everything from private salary negotiations to alimony payments.

Broken compass

There’s a whole other story to tell about exactly what was done to the CPI that resulted in benign inflation readings.

In 1983 home prices were replaced with “owner occupied equivalent rent,” which is a made-up number for how much homeowners would charge themselves to rent their house to themselves. In practice, this resulted in a reduction in measured inflation compared to the pre-1983 CPI calculations using the same data and, it stands to reason, at least contributed to the “taming of inflation” for which Volcker is credited today.

But by the end of the 1980s, even the “improved” CPI was showing inflation on the rise. In 1990, Social Security saw a COLA increase of 5.4% (which would have been higher without the 1983 change). Further changes would be required to keep things from going off the rails.

The early 1990s saw two more changes: “hedonic adjustments” and “substitutions.”

Hedonic adjustments introduced a way for actual price increases to be transformed into price decreases. Imagine that last year a television set cost $300 and this year it costs $400. That price increase would indicate that inflation is, depending on how you do the math, somewhere between 25% and 33%.

But what if that $400 TV had a better screen resolution? Instead of 1080p, it was 1440p. The BLS might determine that, although the purchase price had increased by $100, the value of that TV had increased by $150 thanks to its improved resolution. That would mean that the adjusted price of the TV was $250 – a savings of $50 and, for inflation purposes, something that would lower the total CPI reading by off-setting other categories which increased in price during the same time period.

Substitutions accomplished largely the same thing in a different way. If the CPI tracks the price of steak and steak is 20% more expensive this year than it was last year, you would think that would result in a higher official measure of inflation. Instead, the BLS says, “Steak is expensive! We’ll substitute ground beef in our inflation measurement in its place because who in their right mind would buy steak at these prices?”

Outside of measuring inflation, that assertion could be correct. Surely many people substitute cheaper products when what they normally buy becomes more expensive. But for the purposes of accurately calculating inflation, it’s nonsensical and obviously undermines that goal.

In practice this second round of changes to how inflation is officially measured further reduced measured inflation.

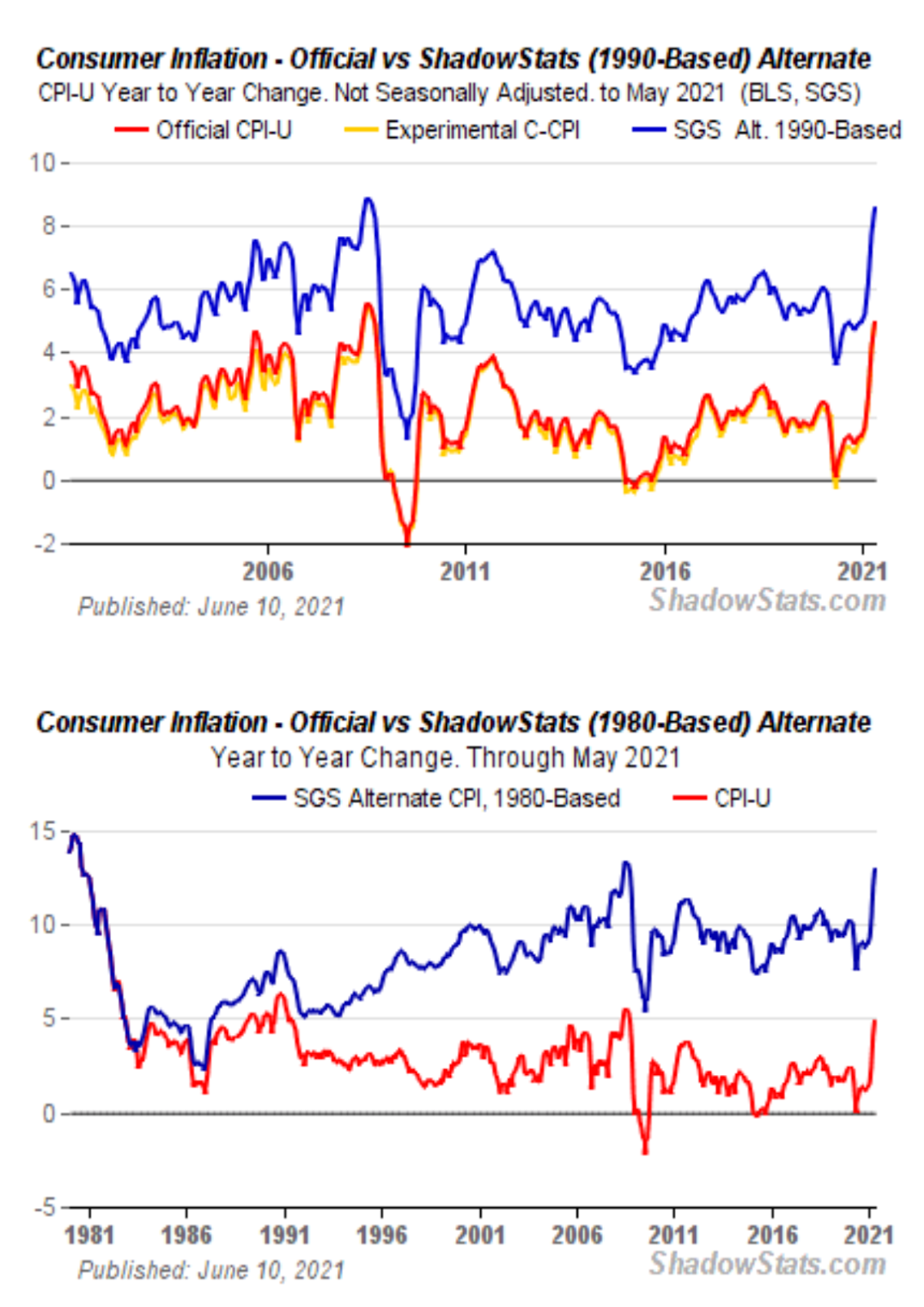

While the government no longer tracks CPI using the original, unmodified methodology, it can still be compiled from available data. Economist John Williams, publisher of “Shadow Government Statistics,” has been calculating the index using the original methods and comparing it against the subsequently revised methodologies since the early 1980s. The resulting picture is pretty sobering:

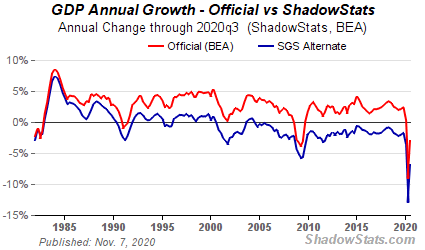

The official misrepresentation of inflation is bad on its own, but has also tainted most of the data we use to make decisions, notably GDP which is exaggerated to the upside (good for whoever is in power) because it is growth minus inflation. If you replay the numbers with actual inflation, we've had mostly negative GDP growth for the last 20 years.

That's despite the incredible productivity gains from the internet and technology broadly, which could lead one to believe that government as practiced in the U.S. has been aggressively detrimental to society and prosperity at all levels.

Like the blue pill in “The Matrix,” the CPI has given Americans a falsely comforting perception of reality. When even this metric jumps 5%, we’d better hope it’s a glitch.

Off the charts

Bitcoin's Puell Multiple shows better days ahead

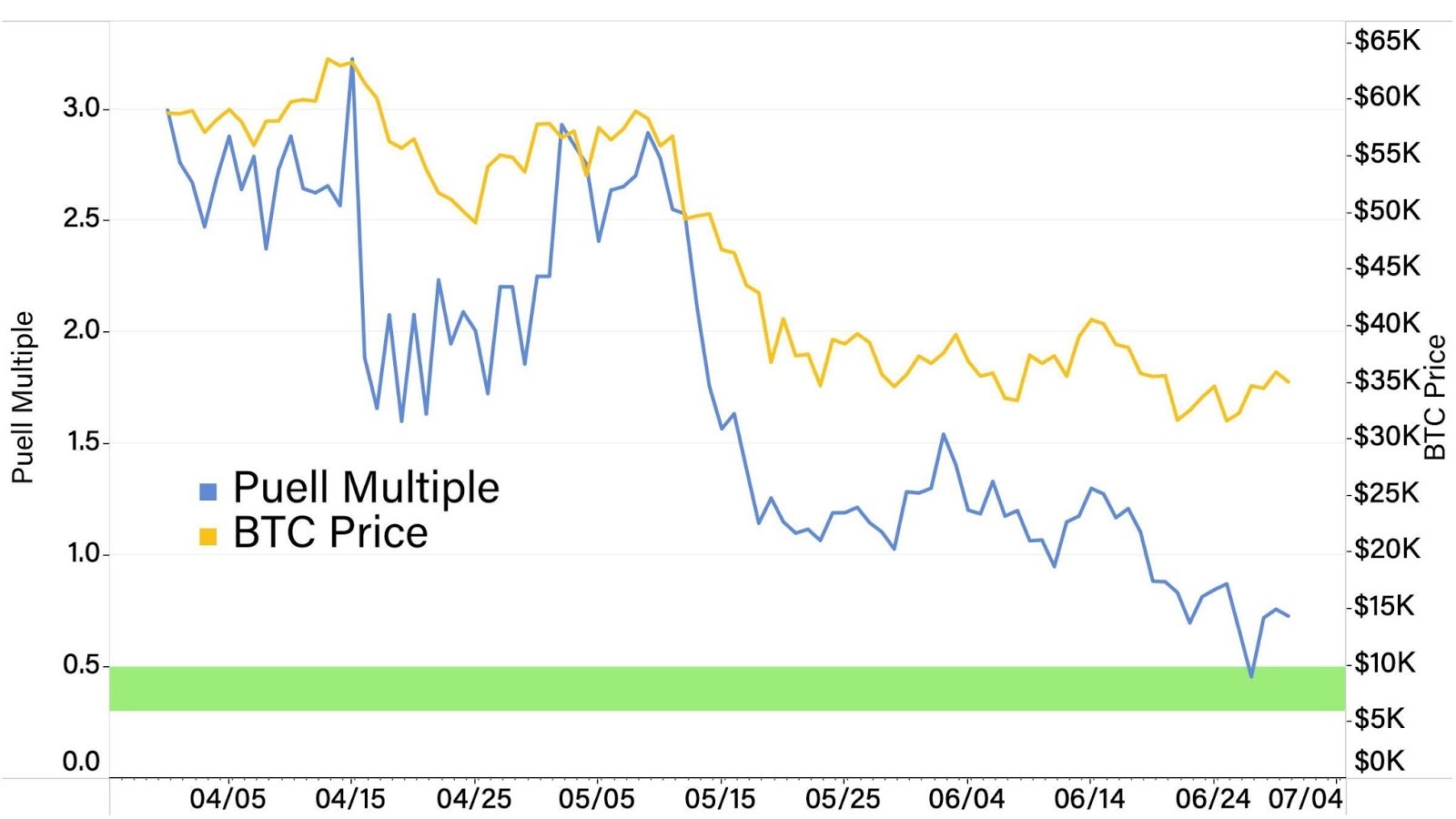

While Bitcoin miners have received an increasingly smaller amount in block rewards over the years, the USD value of their rewards peaked in 2021 Q2 as BTC price hit a new all-time price high of $64,889. By the end of the quarter, BTC plummeted 46% off its price high, pushing miner revenue back down to pre-bull market levels.

Analyzing bitcoin miner revenue can reveal important insights about the timing and magnitude of crypto market cycles. The Puell Multiple is a metric that is often used to identify market peaks and troughs by measuring periods of time in which miner rewards are overvalued or undervalued, compared to historical returns.

The Puell Multiple is calculated by dividing the daily issuance value of bitcoins in dollars by the one year moving average of daily issuance value. The green zone from 0.3 to 0.5 in the Puell chart here has historically been a support zone and a strong indicator that bitcoin price has found a bottom.

Since 2012, the Puell Multiple has dipped into the green zone a total of six times. Notably, each dip has been followed by a bitcoin price surge. A few notable Puell bottoms are November 2011, before bitcoin moved from $2.50 to $950, December 2018, where bitcoin ran from $3,500 to $12,500 in the following seven months, and March of 2020.

Last month, the Puell multiple appeared to find support briefly in the green zone and now we wait to see if history repeats itself.

Sign up to receive Money Reimagined in your inbox, every Friday.

DISCLOSURE

The leader in news and information on cryptocurrency, digital assets and the future of money, CoinDesk is a media outlet that strives for the highest journalistic standards and abides by a strict set of editorial policies. CoinDesk is an independent operating subsidiary of Digital Currency Group, which invests in cryptocurrencies and blockchain startups. As part of their compensation, certain CoinDesk employees, including editorial employees, may receive exposure to DCG equity in the form of stock appreciation rights, which vest over a multi-year period. CoinDesk journalists are not allowed to purchase stock outright in DCG.